The Palisades fire started burning on the morning of January 7, identified, per early reports, by an immense cloud of smoke rising from the Santa Monica mountains. By noon it had expanded to 200 acres, necessitating mandatory evacuation orders, and by 3:30 p.m. the fire had grown to six times the size, burning across 1,262 acres. I read the news reports in a dreamlike state, my phone balanced precariously between the arm of the rocking chair and the breastfeeding pillow around my waist that had come to feel like a plush appendage. Luka was just 18 days old and cluster feeding endlessly.

Everything I know about California wildfires I learned from Joan Didion, and as a New Yorker with a penchant for travel farther and farther east, what happens on that coast can sometimes feel like lore. In my mind, even the Santa Anas were more of a literary phenomenon than a hot, deadly wind capable of indiscriminate destruction. But this time the photos of charred landscapes and skeletons of blackened houses touched a nerve. These fires seemed different – worse – like everything else going on in the world.

The day Luka was born we arrived at the hospital at 6 a.m. sharp for the planned cesarean section I had opted for in lieu of induction or simply waiting for the onset of spontaneous labor. I can’t say I was excited about the surgical removal of my baby, and I did wonder if I was forfeiting a sacred rite of womanhood by foregoing a vaginal birth, but by the 40th week of my pregnancy, with no signs of labor to speak of, and encumbered with a belly that looked and felt large enough for twins, I decided that the few downsides of a c-section did not outweigh my fear of third degree perineal tears or organ prolapse or stillbirth — however likely or unlikely — and I was at peace with my decision.

The procedure itself was seamless — under two hours from the time they placed the IV in my arm to the time I was wheeled into the recovery room. It was, however, the opposite of “natural.” As expected, the OR was freezing cold and steely, with an operating table in the center that looked like a padded cross. When I entered, the nurses were performing a kind of surgical instruments roll call, reciting the names of each scissor, retractor, scalpel, and forceps aloud before placing them carefully on sterilized trays. I was wearing an open-backed hospital gown and visibly shaking from cold and nerves, but in time I found their processes strangely calming. The residents introduced themselves and their specialties, and the anesthesiologist walked me through the spinal block procedure. As the time ticked closer to the appointed hour I felt the anxiety rise in my chest – I had undergone surgery before, but not awake surgery that involved bringing another human being into the world.

The rest is a blur. I remember my doctor holding my hands and telling me to crunch forward as the anesthesiologist placed the needle in my back. Then the drape went up and Ilia was in the room and there was “pressure” on my abdomen that one of the surgical residents acknowledged as “so intense, right?” in response to my alarmed “wowww.”

And then I heard my baby wail as his chubby pink body appeared in view and my OB exclaimed, “He’s huge Jess!” I remember saying, “Hi, baby!” as I reached out to touch him across the drape, but he was whisked away for the standard post-birth procedures and Ilia began an excited narration: “They’re weighing him now, eight pounds eight ounces! And measuring, 20 inches long! Now they’re washing and swaddling him and putting some medication on his eyes. He’s got strong lungs! 10 fingers, 10 toes. Everything looks amazing. I’m bringing him over now!”

Then his puffy little cheek was on my cheek, and I was overcome with relief and exhaustion. I remember wondering if my reaction was normal. Perhaps I should be crying for joy? But the immensity of the moment – and probably the drugs – left me feeling more stunned than verklempt, and I simply voiced the emotions I knew were there: “My baby is here, I’m so happy, I’m so happy.”

All of the photos from the two hours after birth show me with my head tilted slightly back, eyes closed, cradling Luka against my breast. I wanted to hold him skin-to-skin forever, and I was amazed that my body was capable of producing the colostrum he needed to be sated. I spent the next two hours in a twilight state, warm and comfortable, engrossed in the movements of my baby, and wishing the doctors and nurses would stop poking and prodding and asking me questions that I could barely focus on long enough to answer.

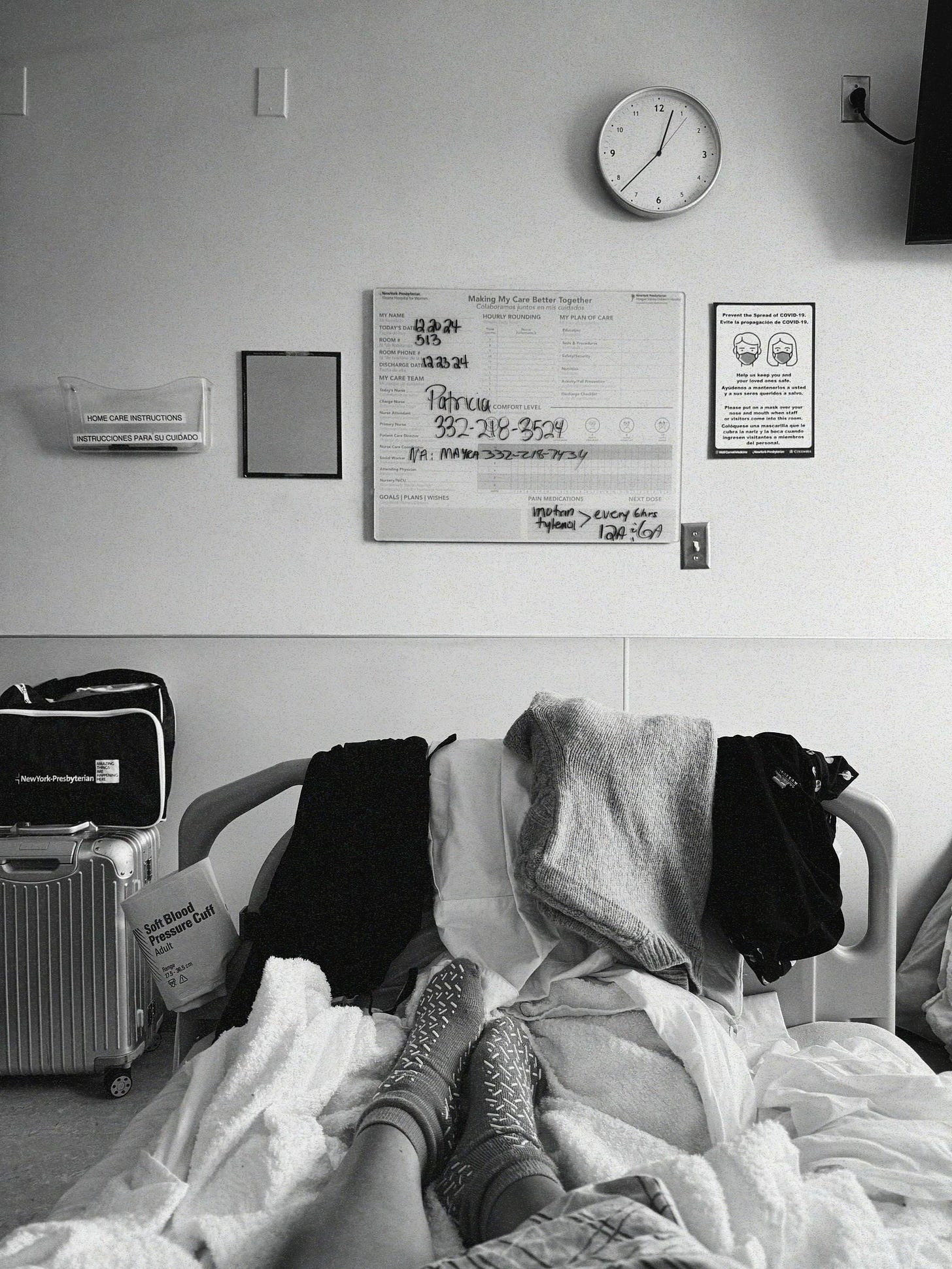

I vomited in the elevator on the way down to the maternity floor and panicked when they put us in the windowless portion of a shared room with another patient who was blaring Spanish language TV and demanding that the heat be turned up to 85. I was sweating and nauseous and feeling claustrophobic – there was barely room for the bassinet beside the bed and the nurses seemed too distracted to care. I knew my hospital experience would be nothing like a Korean joriwon, but the facilities and the care (at one of New York City’s preeminent hospitals no less) left much to be desired. After some protestation and not insignificant tears we were moved to our own room. The refrigerator clanged unpredictably, and instead of heat there was air conditioning, but with space to breathe and Luka snuggled next to me all felt right in the world.

The next two days were a constant flow of doctors, nurses, lactation consultants, social workers, pediatricians, even hospital photographers. There was a regimen of painkillers and a checklist of protocols. There were hearing tests and weigh-ins, and instructions on wound and baby care. The first time I stood up to walk I felt like I might cleave in two, but I spent most of my time at the hospital recumbent, feeding Luka around the clock, the warm weight of him becoming a part of me.

It was a mere 20 degrees on the day we were discharged from the hospital, and a light snow covered the ground. My feet had swollen larger than my loafers, a predicament I had not anticipated, and I felt ridiculous as I padded on stockinged feet toward the car. We struggled to fold the Doona and lock it into the backseat as Luka wailed from within — he had been upset since I changed him into his “going home outfit,” a white pointelle knit set with matching bonnet that had been gifted for the occasion. My romanticized version of our departure had been thoroughly upended, and as the nurses waved goodbye and sent us on our way I felt slightly dysfunctional and a little overwrought.

The traffic was considerable for a Sunday, and as we approached Exit 31 on the BQE, two speeding cars in a game of chicken collided next to us. One car was thrown into the shoulder and crumpled like a piece of tin foil, and the other crashed into the wall of cars queuing to exit onto Wythe Avenue. The driver was ejected into the roadway, screaming and bloody, and as we swerved away from the carnage, I was shaken and trembling. The world felt far too harsh and menacing for the tiny, vulnerable life beside me.

In the weeks that followed, we settled into a cadence of actions necessary to sustain a life. The days blended into one another and we celebrated the little feats, like a nice, wide latch; milk drunk smiles; big burps; a few extra minutes of sleep. What was once understood in the abstract we felt in our tired bodies: babies are so irreversible and such tiny monsters of need.

If I were to be specific, I would say the most difficult part of those first days of motherhood was feeling the throb of postpartum hormones coursing through my body, bringing on short periods of melancholy on a moment’s notice. It was the overwhelming anxiety that rolled in like a tidal wave at sundown each day as another sleepless night loomed large. It was the guilt I felt when looking at Winston, knowing he would no longer benefit from the lion’s share of attention he was so accustomed to receiving. It was and still is the shift in identity, the relinquishment of one kind of work (cerebral, social) and the acceptance of another (nurturing, solitary).

In those early days I nursed Luka to sleep and watched the world burn. I read the news obsessively in anticipation of the inauguration of a thug and a tyrant. I worried about the far left, the far right, and the climate. About the wars in Gaza, in Sudan, in Ukraine. About trade and immigration and foreign aid. I tried to fathom what a hateful and ignorant administration would mean for the future of this country and the life of my newborn son.

What a time to bring a person into the world, I thought. Or is it always like this, no matter the era? In any case, I concluded that motherhood would require courage; it is not for the weak.

On January 9 the Palisades fire had burned more than 27,000 acres, the Eaton fire had grown to more than 10,000 acres, and both were 0% contained. I pulled out my red cloth-bound edition of Didion’s non-fiction to read “Los Angeles Notebook,” an essay in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She begins:

“There is something uneasy in the Los Angeles air this afternoon, some unnatural stillness, some tension. What it means is that tonight a Santa Ana will begin to blow, a hot wind from the northeast whining down through the Cajon and San Gorgonio Passes, blowing up sandstorms out along Route 66, drying the hills and nerves to the flash point. For a few days now we will see smoke back in the canyons, and hear sirens in the night. I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is due, but I know it, and almost everyone I have seen today knows it too.”

She describes the kind of wind it is:

“The Santa Ana, which is named for one of the canyons it rushes through, is a foehn wind, like the foehn of Austria and Switzerland and the hamsin of Israel. There are a number of persistent malevolent winds, perhaps best known of which are the mistral of France and the Mediterranean sirocco, but a foehn wind has distinct characteristics: it occurs on the leeward slope of a mountain range and, although the air begins as a cold mass, it is warmed as it comes down the mountain and appears finally as a hot dry wind. Whenever and wherever a foehn blows, doctors hear about headaches and nausea and allergies, about ‘nervousness,’ about ‘depression.’ In Los Angeles some teachers do not attempt to conduct formal classes during a Santa Ana, because the children become unmanageable. In Switzerland the suicide rate goes up during the foehn, and in the courts of some Swiss cantons the wind is considered a mitigating circumstance for crime. Surgeons are said to watch the wind, because blood does not clot normally during a foehn. A few years ago an Israeli physicist discovered not only during such winds, but for the ten or twelve hours which precede them, the air carries an unusually high ratio of positive to negative ions. No one seems to know exactly why that should be; some talk about friction and others suggest solar disturbances. In any case the positive ions are there, and what an excess of positive ions does, in the simplest terms, is make people unhappy. One cannot get much more mechanistic than that.”

She concludes:

“It is hard for people who have not lived in Los Angeles to realize how radically the Santa Ana figures in the local imagination. The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself: Nathanael West perceived that, in The Day of the Locust; and at the time of the 1965 Watt riots what struck the imagination most indelibly were the fires. For days one could drive the Harbor Freeway and see the city on fire, just as we had always known it would be in the end. Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse, and, just as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.”

I think motherhood, too, brings us closer to the edge of things. The shift I experienced postpartum is greater than any mental or physical change I have ever known, heightening a sense of vulnerability but also deepening the capacity for love. Motherhood diminishes and widens the scope of one’s identity: a mother is diminished, at least temporarily, to a person who exists to sustain a life, but she is widened, or perhaps more accurately, she is forever endowed with the ability to love and care for another human being in a way theretofore unimaginable.

One early morning in January, dazed and half asleep, I startled myself awake as I glanced in the mirror. I recognized in my face the likeness of a person I knew intimately, but who was not me. I realized it was Luka I saw mirrored back, the face of the sweet baby I had been studying night and day, a part of me but wholly his own.

Loved reading about your experience during your new life of motherhood, and the continuing story of bringing this beautiful baby, Luka, home, and the love you have for him.

Well written ❣️